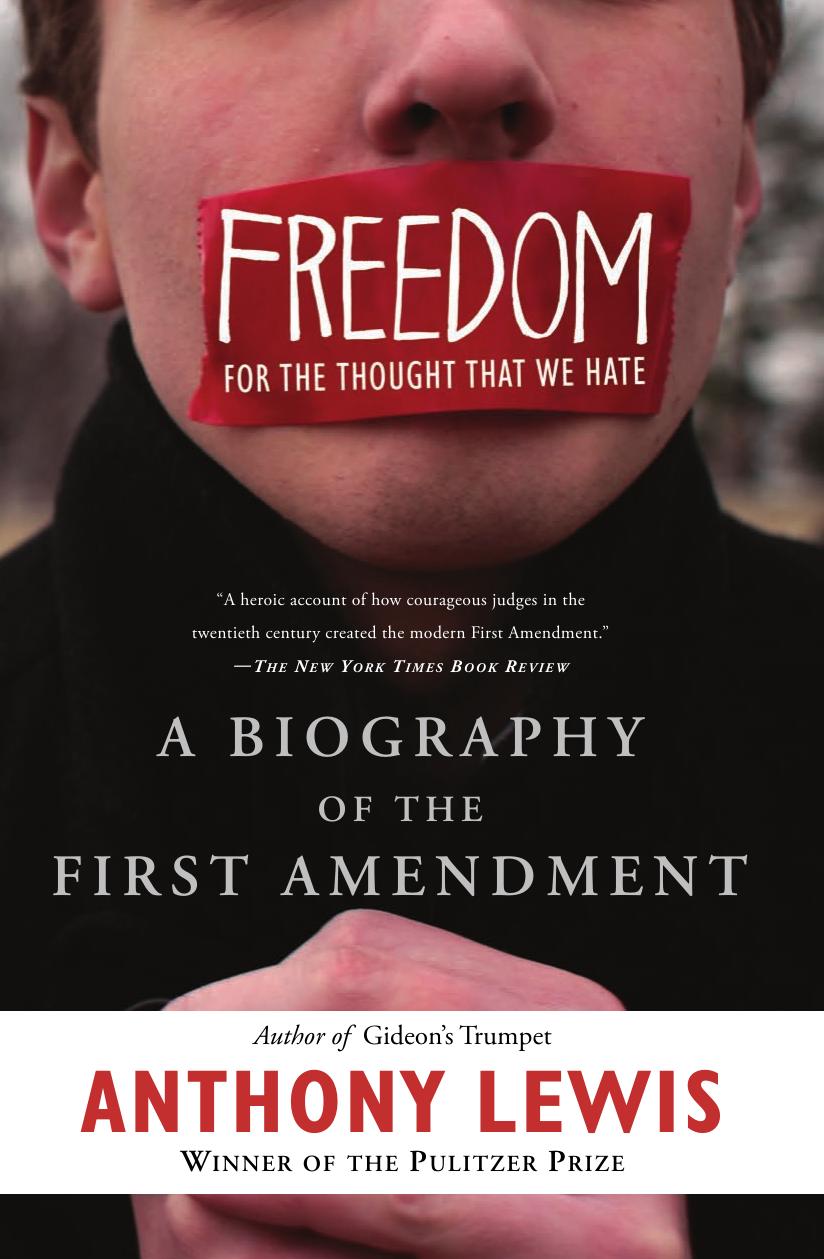

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate by Anthony Lewis

Author:Anthony Lewis

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Basic Books

Holmes’s astringent characterization of Gitlow’s manifesto as a “redundant discourse” put this case—and others like it— in realistic perspective. Benjamin Gitlow was not a threat to American society. Decades later, one can only wonder why the authorities bothered with him. The same was true of hundreds of prosecutions brought under state statutes like the Montana sedition law and the federal Espionage and Sedition Acts. But the majority of the Supreme Court was still fixed on upholding the convictions of radicals whose words might have a “tendency” of which they disapproved. (The Gitlow decision was in fact important for another reason. The majority opinion, by Justice Edward T. Sanford, for the first time accepted the argument that the First Amendment’s protections of speech and press from federal repression were applied to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment. From then on, most of the development of First Amendment freedoms came in state cases.)

In 1937 the Supreme Court made two decisions that turned away from fear of radicalism. In De Jonge v. Oregon, Dirk De Jonge had been convicted of violating Oregon’s criminal syndicalism law when he helped to conduct a meeting held under the auspices of the Communist Party. There was no charge that “criminal syndicalism” or violence was advocated at the meeting. The sole basis of the conviction was the fact that the Communist Party had called the meeting.

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed De Jonge’s conviction. The opinion, by Chief Justice Hughes, did not take up the debate about whether there was a clear and present danger of some substantive evil. Instead, the chief justice focused on the general importance of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, which is also protected by the First Amendment. (“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”) Hughes wrote: “The right of peaceable assembly is a right cognate to those of free speech and free press and is equally fundamental. . . . Peaceable assembly for lawful discussions cannot be made a crime. The holding of meetings for peaceable political action cannot be proscribed. Those who assist in the conduct of such meetings cannot be branded as criminals on that score.”

Dirk De Jonge was in a different legal situation from that of Benjamin Gitlow and the others who had lost all the early cases. But underneath those differences one can sense a change in judicial attitude, a much greater sensitivity to the demands of free expression. De Jonge would not have prevailed in 1919, when the Abrams case was decided over Holmes’s dissent, or in 1927, when Anita Whitney’s was.

The 1937 Court had greater difficulty in the case of Herndon v. Lowry, decided in favor of a free-speech claim by a vote of 5 to 4. Angelo Herndon was a black man who acted as an organizer for the Communist Party in Georgia: a role that must have required extraordinary courage.

Download

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate by Anthony Lewis.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Day by Elie Wiesel(2249)

The Age of Genius by A. C. Grayling(2175)

Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad by Gordon Thomas(1955)

The Gulag Archipelago (Vintage Classics) by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn(1730)

FATWA: Hunted in America by Pamela Geller(1724)

Columbine by Dave Cullen(1500)

Examples & Explanations: Administrative Law by William F. Funk & Richard H. Seamon(1332)

The Rule of Law by Bingham Tom(1320)

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit(1316)

Anatomy of Injustice by Raymond Bonner(1270)

Three Cups of Tea by Greg Mortenson(1261)

ADHD on Trial by Michael Gordon(1243)

That Every Man Be Armed by Stephen P. Halbrook(1241)

Gideon's Spies by Gordon Thomas(1218)

Palestinian Walks by Raja Shehadeh(1144)

The Source by James A. Michener(1137)

Fast Times in Palestine by Pamela Olson(1122)

Nothing to Envy by Barbara Demick(1042)

Constitutional Theory by Carl Schmitt(1038)